This post was co-written with Peter Carbonetto, Ph.D., Computational Biologist at AncestryDNA

For every AncestryDNA customer, we estimate the ethnic origins of their ancestors from their DNA sample—what we call a “genetic ethnicity estimate.” AncestryDNA customers can currently trace their ancestral origins to specific parts of the world, including 26 regions across Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Since the AncestryDNA science team is always on the lookout for ways to improve our genetic ethnicity estimates, we were excited about the appearance of a new scientific article in the journal Nature, “The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population.” How well do their findings match up with patterns of genetic ethnicity for individuals with British ancestry at AncestryDNA?

In the study, researchers at several universities, including University of Oxford, attempted to learn about historical trends from the DNA of people living in the United Kingdom today. They reconstructed a detailed portrait of the history and diversity of the British Isles from the DNA of over 2,000 people with deep roots in the UK – one of the most comprehensive collections of genetic data from the UK to date. The study reports several new discoveries, several of which are of particular interest to us at AncestryDNA. While their findings suggest the potential for more detailed ethnicity estimates for people of British ancestry, the study also illuminates some of the challenges in pinpointing British origins from DNA.

Teasing apart the geographic origins of British and continental European DNA is extremely challenging due to the complex history of Europe. Individuals with ancestors from Britain might find that their AncestryDNA ethnicity estimate has a lower proportion of “Great Britain” than they might expect. In fact, it is common for even individuals with all four of their grandparents born in Britain to have much less than 100% of their ancestry assigned to Great Britain.

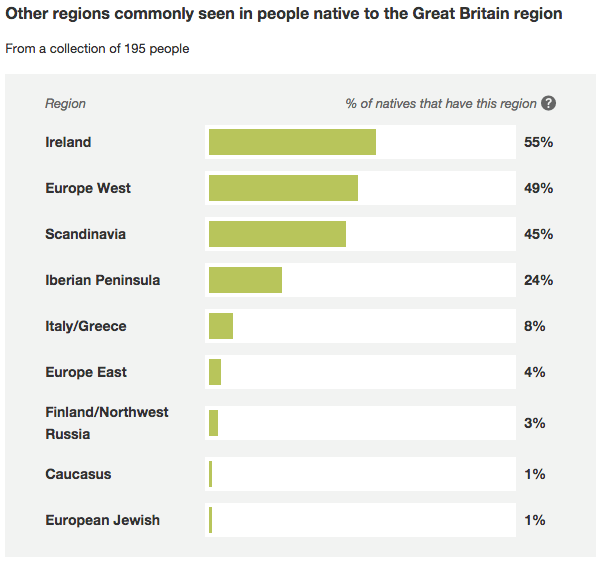

Such estimates are due to the fact that there has historically been continuous, frequent genetic exchange between Great Britain and neighboring regions of Europe. In other words, people have moved to and from the British Isles a lot over the past thousand years or so, and their DNA has been shared with other groups in complicated ways. For example, we find that Europe West, Scandinavia, and other regions often appear in the ethnicity estimates of people with deep ancestry in Great Britain.

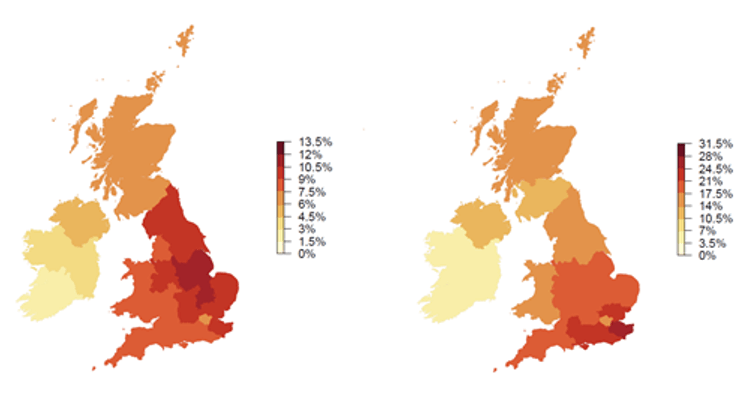

In our continued research into ethnicity estimates for individuals born in the UK, we also discovered that the proportion of DNA attributed to such continental European ancestry even varies by location in the UK. For example, we find the greatest concentration of Scandinavian ancestry in the East Midlands and Northern England, and we find higher proportions of Europe West ancestry in the South East of England.

These patterns of genetic ethnicity for individuals with British ancestry at AncestryDNA complement those in the recent study published in Nature. For example, one major finding of the Nature paper highlights the incredible genetic diversity of the British Isles: DNA from Western German, Northern Belgian, Danish and French parts of continental Europe all have contributed heavily to the DNA of individuals across the British Isles. This likely reflects past migration events into the UK, including Roman occupation, settlement of Saxons from the Danish peninsula, and the Norman invasion (see Figure 3 of the study). The Nature study reinforces the difficulty of estimating genetic ancestry in the British Isles because of its complex history.

However, the study also showed that by identifying “clusters” of individuals based on their DNA, the British Isles itself can be subdivided into different regions. Some parts of Britain, such as Wales, the Orkney Islands, and a third region that includes Scotland and Northern England were found to be highly genetically differentiated from other regions. On the other hand, a single genetically homogenous “cluster” covers most of central and southern England – meaning that further subdividing this region is difficult with genetic data alone (see the red dots in Figure 1 of the study).

These results suggest the potential to subdivide Great Britain ethnicity estimates into finer-scale regions, including Wales, Scotland and the Orkney Islands. Realizing this possibility for our AncestryDNA customers would require the right statistical tools and adequate DNA samples from the British Isles. First, we need to obtain adequate genetic data from individuals with deep ancestry in these regions. Second, more basic research is needed to translate these results to individualized ethnicity estimates. The Nature study only examined trends in the genetic data, and did not attempt to calculate ethnicity predictions for individual people. Despite these challenges, these new findings suggest the exciting potential for providing more detailed estimates of British ancestry from DNA.

In summary, the complex genetics of the modern-day British mirrors the complicated history of England and the British Isles. Thus, while the study underscores the challenges of estimating Great Britain ancestry from genetic information, at the same time it highlights potential ways to provide more detailed ethnicity estimates within Great Britain. As we continue to improve and refine our ethnicity estimates at AncestryDNA, we’ll continue to survey the latest science to enhance our customers’ discoveries of their ancestral origins.