Â

“Happiness often sneaks in through a door

you didn’t know you left open.â€

~ John Barrymore

The holiday season and family get-togethers provide a great opportunity for family historians to glean information from relatives that can further your research. Whether you are planning on conducting formal interviews or just a little discreet prying, a little pre-planning can go a long way. Take some time to review what you know and what information you need to know. Then come up with a list of questions, the answers to which may give you some guidance. Check out the list of interview questions in the Ancestry Library for some ideas.

This year our daughter began taking pre-Algebra in school and she didn’t really get off to a smooth start. Accustomed to figuring out problems in her head or on a separate piece of scrap paper, she turned in her first homework assignment only to get it back with points taken off because she didn’t show her work. She was crushed. I tried to explain the rationale behind the grade and the importance of showing her work. It was a tough lesson for her but something that she’ll need for years to come. And if she chooses to follow her mother’s footsteps (Hint!), showing her thought process will be a huge help when applied to family history.

When I started writing for the newsletter, the benefits of writing about my genealogical finds became immediately clear. I’m notorious for scribbling cryptic notes in the heat of the moment. Too often, I have made an exciting discovery only to go back to it weeks or months later scratching my head and wondering what the heck I meant. “Corn, fruit, Bkln. 1850?” Is that a grocery list or something to do with my family history? As it turned out, it was a note about a probate to remind me that there was a Cornelius Kelly who had a fruit stand in Brooklyn in 1850–but that’s a story for another day.

Fortunately, when I slip up I can sometimes find a paper trail in the form of an article I have written about the find. But that’s not always the case, so I’ve since expanded the process of “showing my work.†Now, when I dive into my family’s history I journal during the process. This gives me an extended research log, and I’ve also learned over the years that the best way to find holes in my theories is to try to write about them. (Unfortunately, some of my best theories seem to self-destruct when I’m up against a deadline.)

What to Include

Here are some of the items that I include in my research journal:

Your Journal’s Format

My process is simple. I just have an open journal (a.k.a., Word document) for each person in his or her folder on my computer, and when I work on that line, I open it up, type in the date, and create my summary using some or all of the above criteria. Mine is free form, but if it’s more helpful to you, you could easily create a template to use each time, then go through and fill in the blanks. Continue reading

A popular tradition found in many American families is the one pertaining to an unknown Native American ancestor. It is usually the great-great-grandmother with a common given name who supposedly was a “full-blood†[fill in the tribe]. It piques our interest and off we go–but in the wrong direction. All too often, we find that the oral history that has been handed down is not accurate, so it’s important to keep an open mind.

A popular tradition found in many American families is the one pertaining to an unknown Native American ancestor. It is usually the great-great-grandmother with a common given name who supposedly was a “full-blood†[fill in the tribe]. It piques our interest and off we go–but in the wrong direction. All too often, we find that the oral history that has been handed down is not accurate, so it’s important to keep an open mind.

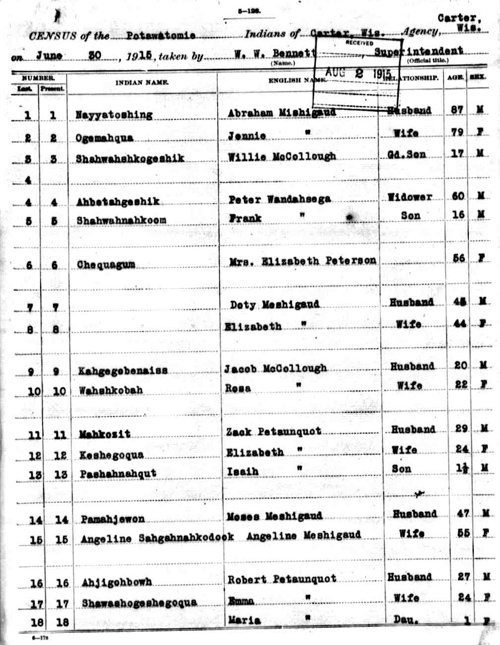

If the name of the tribe is known with certainty, you will be able to take a shortcut and go directly to the tribal records. The U.S. Indian Census Schedules, 1885-1940 (click on the image to see an example from Ancestry.com), or the 1900 population schedule with its “Special Inquiries Relating to Indians†section, and will in many instances provide the name of the tribe and degree of blood. In the case of the 1900 census one question asked the degree (percentage) of white blood an individual had. In many instances, the answer is incorrect. One of my ancestors is listed as 1/8th white, when he actually was 1/8th Cherokee and 7/8th white. Another relative and his children are all listed as white in the 1900 California census, when in fact the children were 1/2 Indian.

You may have Indian blood although your ancestor left the tribe long ago and intermixed with other ethnic groups. Tribal membership and Indian bloodlines are not synonymous. Indian ancestry does not of itself entitle an individual to any special rights or benefits or guarantee eligibility for tribal membership today. Additionally, Indian census lists do not prove tribal affiliation–you must find the enrollment lists and then make the genealogical link that proves that a particular George Wolf or Mary Pumpkin (for example) on that list is yours. Continue reading

If you have ancestors whose surnames begin with “Mc†and “Mac,†such as McKnitt and MacTavish, you may find them suspiciously absent in records even in places you are almost positive they should be appear. Sometimes the Mc or Mac may have been omitted by the person making the record or the record may have been misfiled under the second half of the name. Look in the records for both the full name and for the shortened version of the name. Of course this would also apply to O’Malley and other surname prefixes that could be separated. Learning to misspell and fracture your ancestors’ surnames can sometimes help you find those missing links.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission Site (www.cwgc.org) has details of all British and Commonwealth servicemen killed in action during World War I and World War II and often has details of next of kin. I found my great uncle on the site—someone I never knew fought in World War I. I also found one of my wife’s relatives who was killed during World War II.

Â

Phil

Hythe, Southampton UK Continue reading

The year was 1901 and it marked the end of the Victorian Era. On 22 January, Queen Victoria died at the age of eighty-one after ruling the United Kingdom for sixty-four years–the longest reign in British history. Her reign is largely remembered as a period of economic and imperial expansion, although her popularity wavered at times.

The year was 1901 and it marked the end of the Victorian Era. On 22 January, Queen Victoria died at the age of eighty-one after ruling the United Kingdom for sixty-four years–the longest reign in British history. Her reign is largely remembered as a period of economic and imperial expansion, although her popularity wavered at times.

The 1901 Census for England was taken on the night of 31 March 1901. Enumeration forms were distributed to all households a couple of days before census night and were to reflect the individual’s status as of 31 March 1901 for all individuals who had spent the night in the house. The following information was requested: name of street, avenue road, etc.; house number or name; whether or not the house was inhabited; number of rooms occupied if less than five; name of each person that had spent the night; relationship of person enumerated to the head of the family; each person’s marital status; age at last birthday (sex is indicated by which column the age is recorded in); each person’s occupation; whether they are employer or employee or neither; person’s place of birth; whether deaf, dumb, blind, or lunatic. (This census is available to Ancestry members with a UK or World Deluxe membership.)

The year had begun with the birth of the Commonwealth of Australia as the British colonies of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria, and Western Australia were united. The occasion was celebrated widely throughout the continent with parades and pageantry.

In the U.S., William McKinley began his second term as president of the United States. His term ended tragically and abruptly when he was shot in September 1901 by anarchist, Leon Czolgosz, at the Pan-American Exposition.

He was succeeded by his vice president, Theodore Roosevelt, who became the youngest president in U.S. history. During his terms as president, Roosevelt earned a reputation as a “trust buster,” who used the Sherman Antitrust Act to dissolve a large railroad monopoly. He also began work on the Panama Canal, fought for conservation of our natural resources, and won a Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating the end of the Russo-Japanese War.

Roosevelt’s invitation to Booker T. Washington, president of the Tuskegee Institute, to dine at the White House angered many in 1901. The Atlanta Constitution reported on 18 October 1901 that, “There is a feeling of indignation among Southern men, generally, that the president should, in the face of his declaration of friendliness toward the people of the south, take this early opportunity to show such a marked courtesy and distinction to a negro.”Â

Contributed by Marilyn G.

Contributed by Marilyn G.

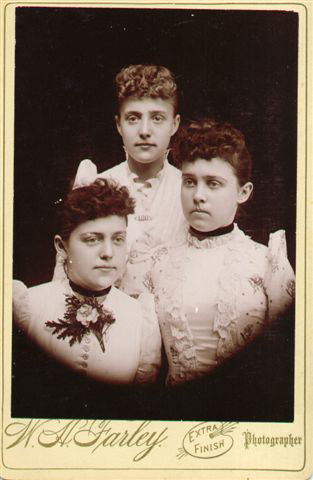

These are the daughters of Frank W. and Serilda Jane Gibson Gates–top Nora, bottom left Emma, right Ella. They grew up in Girard, Illinois.

Click on an image to enlarge it.

Contributed by Delia Ann Jones

Contributed by Delia Ann Jones

This is George W. Hoover in his Union Army uniform. He was a relative of Herbert Hoover and served in Company A, 11th Cavalry Regiment Ohio, 1861-1865.

MyCanvas (formerly AncestryPress) has just launched a new product. You can now create personalized calendars and I’ve already had some fun with them today. You can customize the cover with a photograph and the title, as well as each calendar page. You can even insert family events and thumbnail photographs into the calendar page or create custom backgrounds for each month. I created this page in about ten minutes with photos I had on my computer. (Click on the image to enlarge it.)

MyCanvas (formerly AncestryPress) has just launched a new product. You can now create personalized calendars and I’ve already had some fun with them today. You can customize the cover with a photograph and the title, as well as each calendar page. You can even insert family events and thumbnail photographs into the calendar page or create custom backgrounds for each month. I created this page in about ten minutes with photos I had on my computer. (Click on the image to enlarge it.)

Stephanie Condie has already put up a helpful blog post with some really creative ideas, so I won’t try to reinvent the wheel here, but suffice it to say, I know what I’ll be working on this weekend!

To sweeten the pot a bit, Ancestry is offering a 20% discount on all MyCanvas products through December 24th, so now’s the time to start those holiday projects. To get the discount, just enter this code at checkout: ANHOLIDAY. Â

Click here to go to MyCanvas and start your holiday project!